Spaces with infinite opportunities

Metal-organic frameworks are opening up exciting and previously unknown doors in many different fields, including the life science industry.

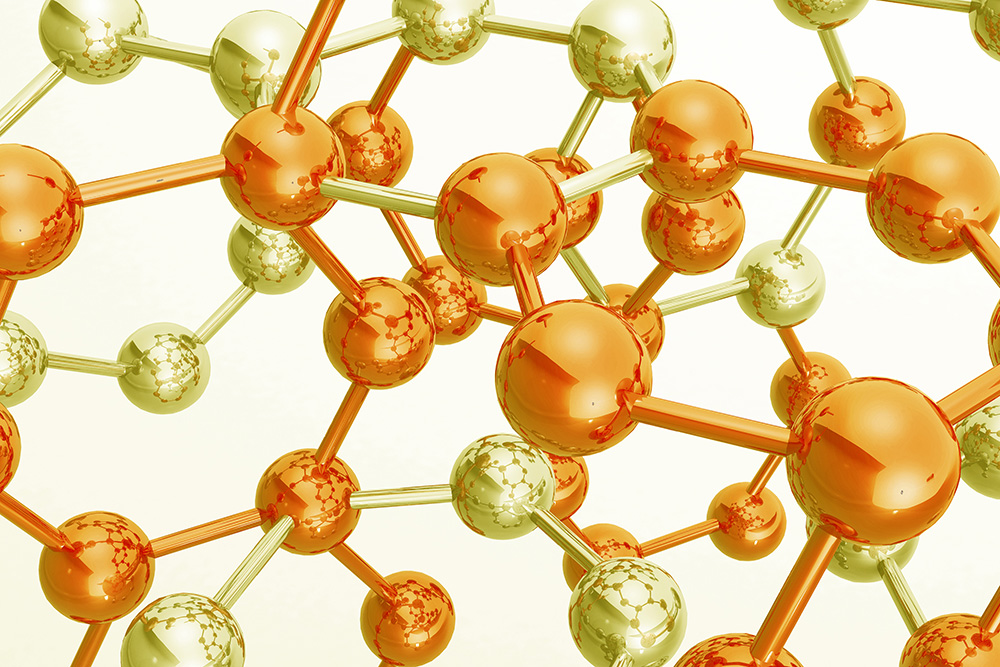

This year’s Nobel Prize laureates in Chemistry, Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson, and Omar M. Yaghi, have been able to create molecular constructions with large spaces through which gases and other chemicals can flow. These constructions have been named metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) because metal ions function as cornerstones in them. The metal ions are linked by long organic molecules and these two components are organized to form crystals containing large cavities. The cavities make the material porous. Having the characteristics of high porosity, chemical versatility, thermal stability, and selective adsorption, MOFs can be used for a number of different cool, exciting, and helpful processes, for example harvesting water from desert air, storing hydrogen, capturing carbon hydroxide, and delivering pharmaceuticals in the body.

MOFs have become one of the most exciting areas in materials science, opening up possibilities for more efficient gas capture and storage, catalysis, and even quantum devices.

“Nobel recognition in this field was long expected, it is a major area not only in chemistry but also in physics,” says Mantas Šimėnas, Professor at Vilnius University’s faculty of Physics, who has been studying these structures for over a decade. “MOFs have become one of the most exciting areas in materials science, opening up possibilities for more efficient gas capture and storage, catalysis, and even quantum devices.”

Šimėnas has co-authored a scientific publication with one of the three laureates, Kitagawa, published in the Journal of Physical Chemistry in 2016. According to Šimėnas, working alongside such a prominent scientist while preparing the publication and obtaining the first results was an immensely rewarding experience for him as a young doctoral student.

“If someone had asked me back then whether he would one day gain recognition from the Nobel Committee, I would have said a firm “yes” without hesitation,” he says.

The discoveries

The story of MOFs begins in 1974, when Richard Robson, who taught at the University of Melbourne, Australia, at the time, was going to drill holes in wooden balls to turn them into atom models. He needed to mark out where the different holes/bonds were to be located, depending on which atom it was, and he realized that the model molecules automatically had the correct form and structure, because of where the holes were situated. He wondered what would happen if he utilized the atoms’ inherent properties to link together different types of molecules, instead of individual atoms.

The ions’ and molecules’ inherent attraction to each other mattered, so they organized themselves into a large molecular construction.

Ten years later Robson tested his idea and combined positively charged copper ions with a four-armed molecule. When combined, they bonded to form a well-ordered, spacious crystal, describes the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. The ions’ and molecules’ inherent attraction to each other mattered, so they organized themselves into a large molecular construction.

He published his findings in 1989 in the American Chemical Society, and shortly after that presented several new types of molecular constructions. He also demonstrated that substances could flow in and out of the construction and that it could be used to catalyze chemical reactions. However, the constructions were still quite rickety and unstable.

The first breakthrough came in 1997 when Kitagawa and his team were able to create three-dimensional constructions that were intersected by open channels.

In Japan, Susumu Kitagawa had also begun to create porous molecular structures. He presented his first construction in 1992, a two-dimensional material with cavities in which acetone molecules could hide. This was not so useful and it was unstable but it had resulted from a new way of thinking about the art of building with molecules, describes the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. The first breakthrough came in 1997 when Kitagawa and his team were able to create three-dimensional constructions that were intersected by open channels (using cobalt, nickel or zinc ions and 4,4’-bipyridine). When they dried one of these it was stable and the spaces could even be filled with gases.

In 1998, Kitagawa presented his findings and the advantages of using these constructions, not least that they can form soft and flexible materials, in the Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan.

In parallel to Kitagawa’s discoveries, Omar Yaghi at Arizona State University, USA, set out to find a more controlled way of creating materials using rational design. In 1995 he published the structure of two different two-dimensional materials, that were like nets, held together by copper or cobalt. The latter was so stable that it could be heated to 350°C without collapsing. He described his findings in Nature and also coined the name “metal-organic framework”. This term is now used to describe extended and ordered molecular structures that potentially contain cavities and are built from metals and organic molecules, explains the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

In 2002 and 2003, in articles in Nature and Science, Yaghi showed that it is possible to modify and change MOFs in a rational manner, giving them different properties.

In 1999, Yaghi also presented an extremely spacious and stable molecular construction, MOF-5 (a couple of grams of which holds an area as big as a football pitch). Kitagawa also presented a material that could change shape when filled with water or methane, and when it was emptied it returned to its original form. In 2002 and 2003, in articles in Nature and Science, Yaghi showed that it is possible to modify and change MOFs in a rational manner, giving them different properties.

Water from desert air

Since these findings were discovered, researchers have developed tens of thousands of different MOFs. As an example, Yaghi’s research group have harvested water from the desert air of Arizona. During the night, their MOF material captured water vapor from the air and when dawn came and the sun heated the material, they were able to collect the water.

They can also act as filters to remove contaminants from water in wastewater treatment.

Many companies are also investing in mass production and commercialization of different MOFs, for example within the electronics industry where MOF materials can contain some of the toxic gases required to produce semiconductors. Companies are also testing materials that can capture carbon dioxide from factories and power stations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. They can also act as filters to remove contaminants from water in wastewater treatment.

Contributing to improved gas separation and carbon dioxide capture, serving as replacements for conventional catalytic materials, and enabling closer integration with biological systems.

The rapid developments in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are expected to accelerate the field of MOFs even further, enabling rapid discovery of optimal structures for specific applications. However, the mass production and new fields of applications have also raised concerns about environmental and health risks, for example through accidental release or deposition of MOFs into the environment that could trigger a range of biological effects. One of the challenges of MOFs has been the lack of clean and sustainable methods to develop the MOF material on an industrial scale.

USD 949.2 million …

… is the expected value of the global metal-organic framework market by 2029, according to BCC Research.

When it comes to future applications of MOFs Šimėnas expects a broader industrial applications, he says, “Contributing to improved gas separation and carbon dioxide capture, serving as replacements for conventional catalytic materials, and enabling closer integration with biological systems.”

Life science applications

There are many actual and potential life science applications of MOFs, including biosensors, drug delivery, imaging, diagnostics, and in pharmaceutical synthesis.

MOFs can for example be employed for targeted drug delivery, as their structures can be tuned to release therapeutic molecules under specific conditions such as pH.

“MOFs can for example be employed for targeted drug delivery, as their structures can be tuned to release therapeutic molecules under specific conditions such as pH. They can also serve as biocatalytic platforms, where their pores help stabilize and protect small enzymes potentially enhancing their activity,” explains Šimėnas.

In biosensors, the structure of MOFs allows them to exhibit luminescence through various pathways like linker emission, ligand-to-metal charge transfer, and metal-to-ligand charge transfer. Their low toxicity and biodegradable nature are further advantages.

Beyond MOFs in Vilnius

Researchers at Vilnius University Faculty of Physics are focused on both the synthesis and the properties of MOFs – the ways in which they respond to their environment and how their structure, electrical, and magnetic characteristics change.

“When we introduce gas molecules into the pores of these materials, we can observe how they attach to the metal centers and how this affects the magnetic properties. When the molecules are released, everything returns to its initial state. These reversible changes make it possible to design sensitive gas sensors,” explains Šimėnas. To understand what happens inside the material, scientists combine electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy and dielectric spectroscopy.

While we did a lot of MOF research five to ten years ago, we’re now more focused on hybrid perovskites – materials that, like MOFs, contain metal centers and organic molecules but have entirely different electronic properties.

Although MOFs remain an important field, Šimėnas’ group is currently focused on next-generation hybrid structures and quantum technology applications, he says. “While we did a lot of MOF research five to ten years ago, we’re now more focused on hybrid perovskites – materials that, like MOFs, contain metal centers and organic molecules but have entirely different electronic properties,” he says.

Research in this field has been greatly strengthened by an ERC Starting Grant of EUR 2.5 million for Šimėnas’ project aimed at increasing the sensitivity of EPR spectroscopy.

“Vilnius University now has one of the most advanced EPR laboratories, as well as strong partnerships stretching from Germany and the UK to the US and Japan. We strive to compete on a global scale – not just in terms of equipment but also in terms of ideas,” concludes Šimėnas.

Published: November 28, 2025