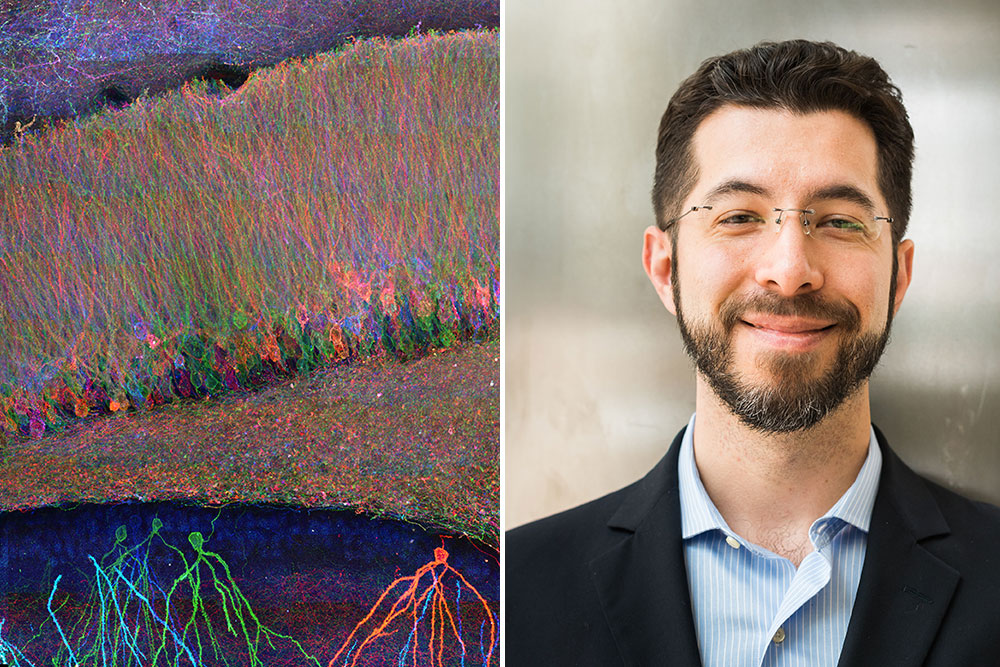

Oskar Hansson: Leading the way in Alzheimer’s research

Lund University’s famous Alzheimer’s researcher, Oskar Hansson, took on a new role in the pharmaceutical industry last year and is today tackling the same challenge from a different angle.

In his new role at Eli Lilly and Company, Vice President of Neurodegenerative Disease Early Phase Clinical and Imaging Development, Oskar Hansson is responsible for phase 1 and phase 2 trials and the development of new brain imaging techniques for neurodegenerative diseases. This will be his main role and focus now, he says, but he will maintain his old role as Professor of Neurology and Group Leader at Lund University.

“I have several very talented employees in Lund who have taken over much of the daily operations,” Hansson says. “I took on this industry role to help accelerate promising therapies into clinical trials and, ultimately, to patients.”

He has also stated to Lund University that besides his main reason, to test new treatment strategies for brain diseases more effectively, he wanted a new challenge in life, “be forced to learn a lot of new things in a short space of time and develop as a person in his professional role.”

From the complex brain to a simple blood test

Oskar Hansson has been interested in neurology ever since medical school. “The brain’s complexity and the unmet needs of patients with dementia drew me to neurology and to research that could change their trajectory,” he says to NLS.

So after earning his MD, he completed neurology training and combined clinical practice with research in neurodegeneration. At Lund University, he has built a translational program to advance diagnostics and deepen the understanding of diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. His team has made significant progress too – not least by developing and validating a new blood test for Alzheimer’s disease.

Initially, the team focused on developing a diagnostic method based on a sample of spinal fluid. The sample had a very high accuracy, but it needs to be taken at specialist clinics in hospitals. Subsequently new techniques have become available that are more sensitive, making it possible to search the blood for markers that indicate Alzheimer’s disease.

Thanks to these new techniques, Hansson and his colleagues were able to develop a blood-testing method that measures levels of Plasma Phospho-Tau217. Studies have shown that the test can detect Alzheimer’s-related changes before symptoms are evident and also track progression as the disease advances. Hansson and his colleagues have also demonstrated that this test is as reliable as, and in some cases superior to, cerebrospinal fluid tests in diagnosing the disease.

Into the clinics

Hansson and his team have also shown the reliability of the blood test when used in routine healthcare settings, including both primary and specialist healthcare. The blood test’s reliability of about 90% was compared with doctors’ assessments within primary or specialist care before they were allowed to see the results of the blood test or cerebrospinal fluid test. Primary care doctors’ accuracy was 61% while specialist physicians were correct 73% of the time.

Dementia diseases affect over 40 million people globally, with Alzheimer’s disease accounting for between 60–70% of cases. One major challenge is that the disease begins its damaging process many years before symptoms appear. Once they appear, there are often limited measures that can be taken. It is therefore truly groundbreaking that a simple blood test can identify people at high risk of being affected early on. That is also why the focus of Hansson’s research has been on completing the blood test so that it can begin to be used clinically. In an ongoing study, Hansson and his team are monitoring 4,000 individuals who do not have symptoms of Alzheimer’s. In the event of early signs of the disease, the individuals are examined with a PET camera, and spinal fluid samples and blood samples are taken to study early changes in the brain.

“The next step is to test drugs early in the process that either remove amyloid or tau, and in this way postpone the onset of symptoms as far as possible,” stated Hansson to Lund University last year.

Inspiration and collaboration

Oskar Hansson is currently one of the most cited researchers in the Alzheimer’s field (he has published over 500 scientific articles) and he has received several prestigious awards, including the Zenith Fellows Award, the Elsa and Alfred Eriksson Prize, and the De Leon Prize in Neuroimaging. Last year he was also named the recipient of the Torsten Söderberg Academy Professorship in Medicine, for his groundbreaking research into biomarkers for neurodegenerative diseases

“I feel strongly about this group of diseases, it gives me energy to do research. Alzheimer’s disease is a common and cruel disease that hits both patients and their loved ones hard,” stated Hansson to Lund University after the announcement and when asked what inspires him.

“Administrative assignments don’t inspire me,” he added. “I love sitting with the doctoral students and postdoctoral fellows to learn about new results and think about what new analyses we should carry out.”

For anyone at the beginning of their career he advises they choose a field of research they feel very passionate about, and where there are still high unmet needs.

“It should nevertheless be an area which is mature enough so that major breakthroughs are realistic in the coming decades. Further, learn rigorous methods, seek great mentors, collaborate across disciplines and sectors, and don’t fear failure – treat it as data and iterate,” he says.

Outside work, he values time with family and friends, enjoys music and reading, and loves playing squash and running in nature.

When it comes to his research, his hopes and expectations are that in 10-20 years, Alzheimer’s disease is routinely detected with simple blood tests long before symptoms, with multiple disease-modifying and preventative treatments available.

“Care will be more personalized, combining biomarkers and digital measures to match the right therapy to the right patient, and hopefully we can ensure that no, or only very few, individuals with Alzheimer’s ever develop dementia,” he concludes.

8 x Milestones by Oskar Hansson

- 2006 and 2012: Publishes two studies showing that spinal fluid tests can predict early development of Alzheimer’s dementia

- 2018: Publishes study showing that PET imaging can detect the protein tau in the brain and thus distinguish Alzheimer’s dementia from other brain diseases

- 2020: The research team describes a new blood test that can detect whether a person with memory problems has Alzheimer’s disease.

- 2021: Shows that the protein tau appears to spread in the brain, often first detected in the temporal lobe and then spreading according to four different patterns. The study establishes that there are at least four different subgroups of the disease with different patterns of tau spread.

- 2021: Develops a simple prognostic algorithm that can accurately predict which people with mild memory problems will develop Alzheimer’s dementia within 2-6 years. The algorithm is based on a simple blood test and three quick cognitive tests.

- 2022: Shows that many people with normal memory who have both tau and amyloid deposits (according to PET imaging) develop memory impairment within 2-4 years. However, if the individual only has amyloid, nothing happens.

- 2023: Accumulation of α-synuclein can be detected in humans even before any symptoms appear. α-Synuclein causes both Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies, and is an independent risk factor for cognitive decline.

- 2024: Study shows that blood tests are even more effective than spinal fluid tests and a safe way to show whether someone has Alzheimer’s.

Source: Lund University

Published: November 18, 2025